From banyan trees with sprawling roots to eucalyptuses with bark that’s rainbow-hued, the trees of Maui span the gamut from resplendent to outlandish.

Each month, we try to shine light on one plant grown on Maui, whether friend or foe, past or present. One such tree worth sharing is the rubber tree.

Otherwise known as the shargina tree, seringueira, rubberwood, or the Para rubber tree, the rubber tree—vibrantly colored and impressively large—played a vital part in Hawaii’s plantation history.

The rubber tree originally hails from the Amazon Rainforest and has long been considered one of the most economically-essential trees in the Western world.

That is, since the invention of the automobile, when widespread cultivation of hevea brasiliensis began to fuel the growing need for rubber. Growing up to 100 feet, the bark of the rubber tree produces a milky latex that can be rendered into natural rubber—the raw material that makes up, among other things, the tires of our car.

Thank Charles Goodyear—yes, he of Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company—for turning rubber into the robust goods the majority of us rely on daily.

In the 19th century, Goodyear made popular modern vulcanization—a chemical process that turns polymers like rubber into a hard-wearing, long-lasting material through the inclusion of sulfur.

Rubber trees proved to be the perfect plant for such a method. Latex is a renewable resource, extraction doesn’t damage the tree, and its harvest is ultra-useful in a number of applications, thanks to rubber’s elasticity and durability (and the fact that it doesn’t conduct electricity). Ultimately, vulcanization of the valuable tree radically changed the face of the industrial world, in that the effective sealing material was used to create the almighty conveyer belt.

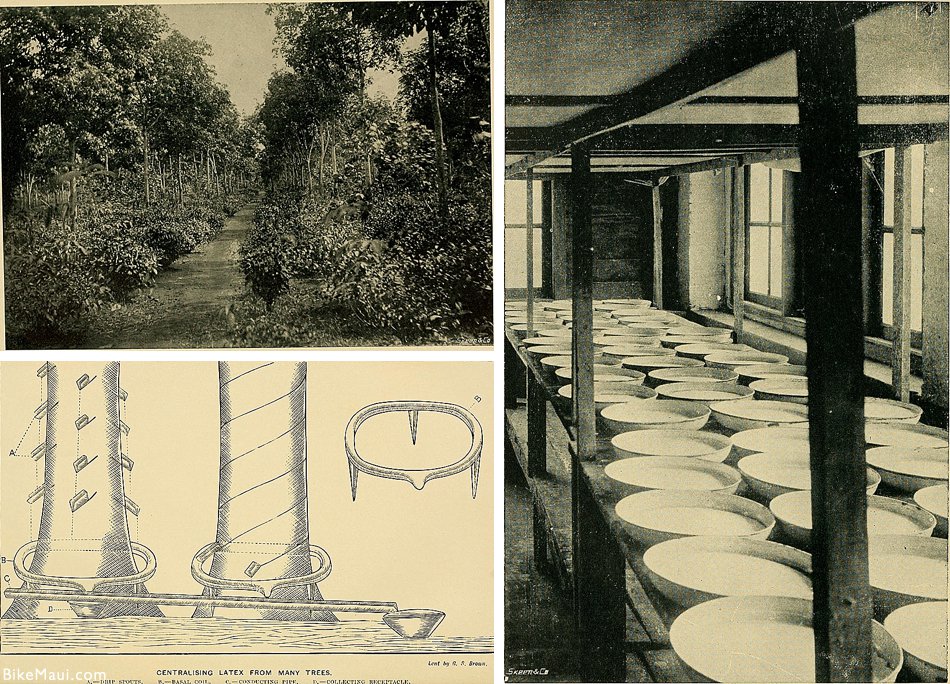

The growing need for rubber also changed the landscape of East Maui (Hana side), when, in 1905, a copse of young rubber trees from Ceylon were imported to the island and planted on Hana’s remote coast—thereby giving birth to the first rubber plantation on American soil.

At first glance, the decision—helmed by Henry Baldwin of Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Co.—was a brilliant one.

Six years earlier, high-quality rubber trees had been planted to determine their viability. The area—one of the wettest in Hawaii—was already home to a thriving forest of trees, including native ‘ohia, koa, hala, and taro, thus suggesting that its fertile grounds would welcome another species. Plus, rubber flourished in other tropical climes throughout the world, particularly in British colonies (where the tree was extensively bred to meet a quickly advancing market). In addition, the Brazilian cities of Belem and Manaus grew rich because of rubber, while the tree took to Western African and Indian soil, ultimately making India the third largest rubber producer in the world.

The rubber trees of Maui, however, told a different story.

While the tree prospered on the island’s eastern flank—where the mix of moist forests and perennial sunshine bear semblance to the Amazon—production of its latex proved to be pricier than anticipated. Laborers in the Third World countries in which it was heavily cultivated were paid a few cents a day; paying workers on Maui $0.50 a day left Hawaiian rubber too expensive for the global market.

Further, while the tree grew well on Maui, the substantial rainfall seen on the island’s eastern shores generated poor quality latex. The age of the trees at the plantation was also of concern: tapping—a process in which incisions are placed on a tree to collect latex—is typically conducted when a rubber tree is six to eight years old. On Maui, tapping began when the trees were two or three years old, which created an irregularity in its amount of bounty. The abundant rainfall further muddied the laborers’ efforts, overfilling the small pans that were used to collect the substance. (In other parts of the world, coconut husks were generally used.) The work itself was arduous: ten-hour days in craggy, volcanic terrain, often awash in rain. A little over ten years later, in 1916, tapping at the plantation ceased—and rubber joined the ranks of sugarcane, sweet potato, silkworms, and other Hawaiian crops whose commercial production was eventually terminated.

But the fast-growing tree—which is propagated through the scattering of its seeds and whose global plantations generate over 28 million tons of natural rubber annually—was resurrected for production during the second World War, when Territorial Governor Ingram Steinback sent 40 Oahu-incarcerated prisoners to restore Maui’s rubber plantation.

The plan? To produce 20,000 to 50,000 tons of rubber per year, thereby furnishing the war effort with the means to fashion everything from Sherman tanks to battleships. Felled rubber trees could (and can) be used as timber; meanwhile, oil from its seeds were utilized to manufacture paints and soaps.

While the scheme failed, what it left in its wake became a boon for Maui’s residents and visitors: over 1500 acres road teeming with one of the industrial world’s most fundamental trees. (It also gave birth to the island’s persimmons, when a Japanese field hand employed at the rubber plantation stashed away enough of his earnings to purchase ten acres of Kula farmland, where he began harvesting persimmons—a russet-colored, autumnal fruit that’s highly revered in Asia.) Plantings have also given to the rubber tree’s rise across Maui, where it’s now found from Wailea and Lahaina to Haiku and Makawao.

If you’re vacationing on Maui, keep an eye out for its telltale magnificence: a swollen trunk—pale to dark brown in color—that gives way to high, branching boughs and explosions of glossy green leaves that can reach up to fourteen inches in diameter. The sight of them is spectacular, but what’s more, these trees galvanized the rise of rubber slippahs as a Hawaiian staple. The shortage of raw materials created by World War II spurred Scott Hawaii—a company that specialized in making rubber boots for local workers—to shift over to the fabrication of rubber sandals. Since then, the rubber “slippah” has become synonymous with Maui’s kickback, surfer creed.“The slipper epitomizes some of the fundamental values of Hawaii’s multicultural history,” Hana Hou magazine affirms, “things like practicality, thriftiness, humility and the unqualified acceptance of each other’s toes.” In other words, the rubber tree is a precious Maui commodity indeed—if not downright indispensable.

Most of the photos courtesy of Photographers in Hawaii.

My Grandfather raised cattle in Nahiku – the rubber trees were his life long enemy. The cows ate the leaves, which gummed up their stomachs. Eventually, they would die, swollen. As kids we would “tap” the tree and roll the sap into balls. We could never make them perfectly round, so when it hardened and we bounced them they would fly off in all different directions. And, because they were raw rubber, they were very heavy.